Ray Dalio: Too Late to Fix Trade-War Fallout

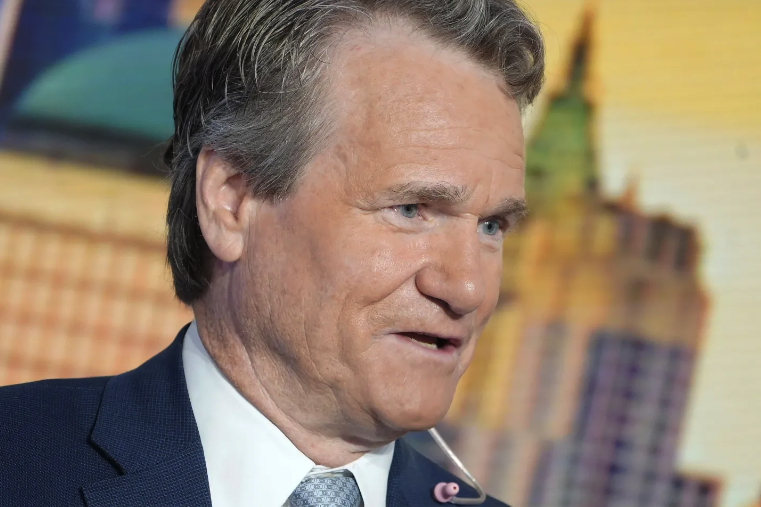

While markets have had a reprieve from the volatility resulting from the Trump administration’s escalating trade war, Ray Dalio, the founder of hedge fund giant Bridgewater Associates, has said the quiet part out loud about the fallout.

In a post on LinkedIn late Monday, he warned that “it’s too late” to undo the fallout from the trade war, warning that the world is “on the brink of the monetary order, the domestic political and the international world orders breaking down.”

That concern was a pervasive undercurrent at last week’s spring meetings of central bankers and finance ministers at the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. The IMF lowered its forecast of global economic growth to 2.8% from 3.3% in January—a call that is still more positive than those from private-sector economists.

Increasingly, economists are pointing to troubling signs, from ocean container bookings from China dropping to retailers warning the administration they face empty shelves within weeks. In a note to clients, Apollo Global chief economist Torsten Sløk noted a survey by the Toy Association of its members about the impact of 145% tariffs on Chinese imports: Nearly half of small and midsize enterprises said they may soon.

Dalio, who has been raising the alarm on the world’s burgeoning debt levels, pushed back on the notion that negotiations will help tariff disruptions settle down. Instead, he said he is hearing from an array of importers and exporters that are already saying it is too late and they are looking to reduce their trade with the U.S. regardless of what happens with tariffs.

“That radically reduced interdependencies with the U.S. is a reality that has to be planned for,” Dalio said. His post comes amid increased chatter about whether investors are losing confidence in U.S. assets, or are reducing their exposure after piling in during a U.S. bull market that lasted more than a decade. It could be both as long-held assumptions about globalization, alliances, and U.S. policies are being tested.

“This one looks like a contemporary version of the old story of how monetary, domestic political and social, and international geopolitical orders change,” Dalio wrote. “There is a growing risk that the U.S., imposing these challenges to deal with, will increasingly be bypassed by a world of countries that will adapt to these separations from the U.S. and create new synapses that grow around it.”

He urges American manufacturers and investors in China, as well as Chinese producers and investors operating in America, to make alternative plans now, regardless of what trade negotiations bring.

Dalio sees the world beginning to come to recognize the need to minimize U.S.-China interdependence and take the risk of conflict more seriously. He also sees a growing recognition that it “is naive thinking” that counterparties will be willing to sell and lend to the U.S. and be repaid for their U.S. debt holdings with dollars that have lost their value —logic that implies that the role of the U.S. as the biggest consumer of manufactured goods and biggest producer of debt assets to finance its overconsumption is unsustainable.

To avoid the far-reaching breakdowns Dalio sees as possible, he said, would require a “calm, analytical and coordinated engineering and implementation,” with a view of the imbalances and need for self-reliance as a shared challenge that could help the U.S. tackle its debt problems.

“Unfortunately, thus far we haven’t seen the better ways and have instead seen disturbing fighting and volatility that are teaching lessons that are leading to irreversible bad consequences.”